04: Tech-xistential Crisis

Takeaways from a minor internet fit, FOMI, and selective unplugging

I took a couple days off to see a friend over an extended weekend. Despite having to plan a trip with precautions front of mind, it feels luxurious to take a break from an already convenient WFH setup. Being out of my house without screens for a few days seemed like a good idea, so I packed an overnight bag full of athleisure clothes and envisioned being outdoors with a good book.

My optimism towards “unplugging” is a function of the growing literature on the toxicity of the internet and the nudges of my online environment. It’s also common for most of my co-workers to take long(er) vacations around this time when school is not in session, and it results in many out-of-office replies that contain well-wishes of time away from technology.

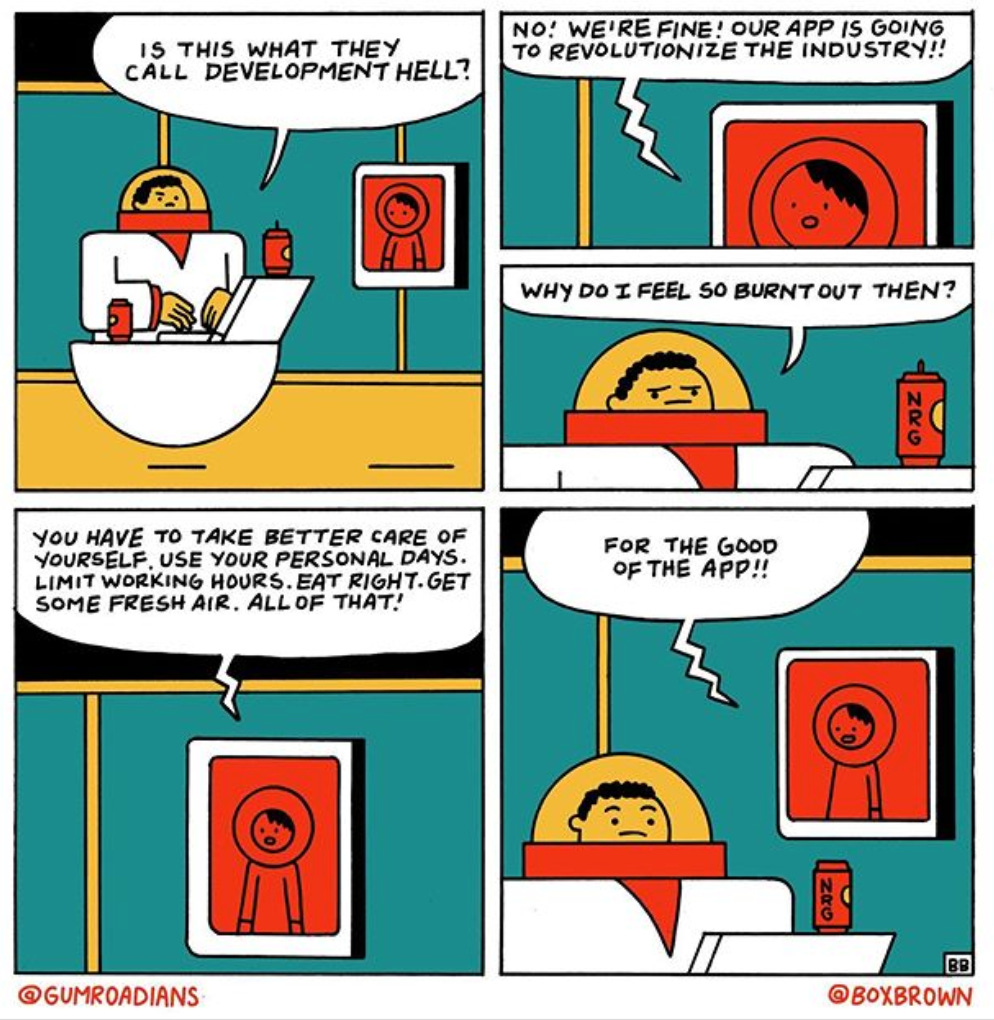

They’re not wrong. The pandemic has exacerbated many things, and internet fatigue is one of them. Even I have never identified with a tweet as much as I did with this one, so I got in the car and left.

Disconnection, and the fear of missing information (FOMI)

Hiking was going to be the main event. It was a good excuse to be outside and not be within six feet of other people. But when the weather in Nevada peaked at 114° and hiking under the sun was bordering punitive, I knew I had enough earth and heat to last me a year.

Even when we weren’t hiking, we were as unplugged as anyone can be: less by choice and more so by circumstance. There happened to be no internet where we were staying, and it wasn’t worth the higher risk of virus exposure to get spotty Wi-Fi in common areas. Even while on the road, I would lose my GPS intermittently and had to depend on a physical map. I felt like I was settling every time I had to listen to the downloaded media on my phone instead of streaming new content. To top it off, it was hard to find restaurants or gas stations in the middle of nowhere.

These tiny inconveniences, while surmountable, are not negligible. They exhausted me in the same way reading trash hyper-partisan news does. I experienced much of what Paul Miller wrote about when he quit online life for a year, except on hyper-speed. In the beginning, he described “how good the absence of the pressures of the internet felt” and how his “freedom felt tangible.” Eventually, though, he found other misuses of his time offline and rediscovered the value of connection.

A compromise for reluctant optimists

I still support unplugging as much as I support any other thing that people do for their mental and physical health. But unlike crosswords, exercising, baking or what have you, I’m skeptical of how ‘disconnecting’ is being marketed like a fad diet instead of a critical skill that needs to be sharpened. “The internet is bad; quit the internet!”

I can never subscribe to that while advocating for digital citizenship and 21st-century skills in the public K-12 curriculum.

A healthy relationship with the internet is, like all other diets, not about consuming all kinds of information all the time or having one source of information all the time. It’s about access to right, reliable information from multiple sources when you need it.

It helped that when I wasn’t complaining about not having cell service, I buried my nose under Andrew Marantz’ book Antisocial. It chronicled the ways in which the democratic internet has been, and is being exploited, under the guise of a techno-utopia. It’s easily one of my best reads this year, sparking conversations in my head about my own consumption. What do we consider mainstream, subculture, fringe, or propaganda? What should and shouldn’t be monetized online? In it is an account of the many perils of social media, and an emphasis on how what’s popular does not necessarily lift up what’s good.

I like being connected in meaningful ways, and it sucks that it has be done in giant response mechanisms that incentivize the amplification of high-arousal emotions. Do I think tech companies hold more power than they know what to do with? Yes. Have people used technology to manipulate, but also democratize art, public opinion, and creation? Absolutely. There’s a lot of exploitative design features and a lack of accountability in what exists, but systems simply do what they are designed to do. Which means it’s always going to be messy—and it means we can always design better. And until they are better, all we have are micro-interventions such as privacy settings and pop-up checkboxes and some good old, self-administered internet fasting.

When I got off Facebook for good, I was certain that “cleansing” wasn’t my purpose. I wanted to recalibrate so I can spend more time on the other parts of the internet that served me more: Twitter, this Substack newsletter, and my many messaging applications.

As soon as I got back to digitally-enhanced life, I reignited my wrist pain and livestreamed Mayor Breed’s conversation with Dr. Grant Colfax about COVID-19 projections for San Francisco. I’ve already laughed at 16 or so internet things and scanned my favorite zoo Twitter accounts for pictures of animals. But best of all, I am able to annoy my fiancé again in real time, which is the most together we’re allowed to be during this pandemic.

As Miller put it, “the internet isn't an individual pursuit, it's something we do with each other. The internet is where people are.” We congregate in new ways online for better or for worse. But the important things still take practice with tools new and old. The pursuit of justice still takes time; building strong relationships online and offline still take work; and filtering the gunk out of the 24/7 news cycle is just as vital a skill as it always has been. Being online in the most intentional of ways allows us to hold the space for the world, not so we can remove ourselves from it, but as a constant reminder of the connectedness of our actions to the actions of others.

Things that made me glad I was online today:

Cats that only respond when called in German

Michael Hobbes’, co-host of You’re Wrong About, A+ take on Cancel Culture

New York City Reaches Milestone With No Reported Virus Deaths